Jewish agricultural colonization in the USSR: continuation.

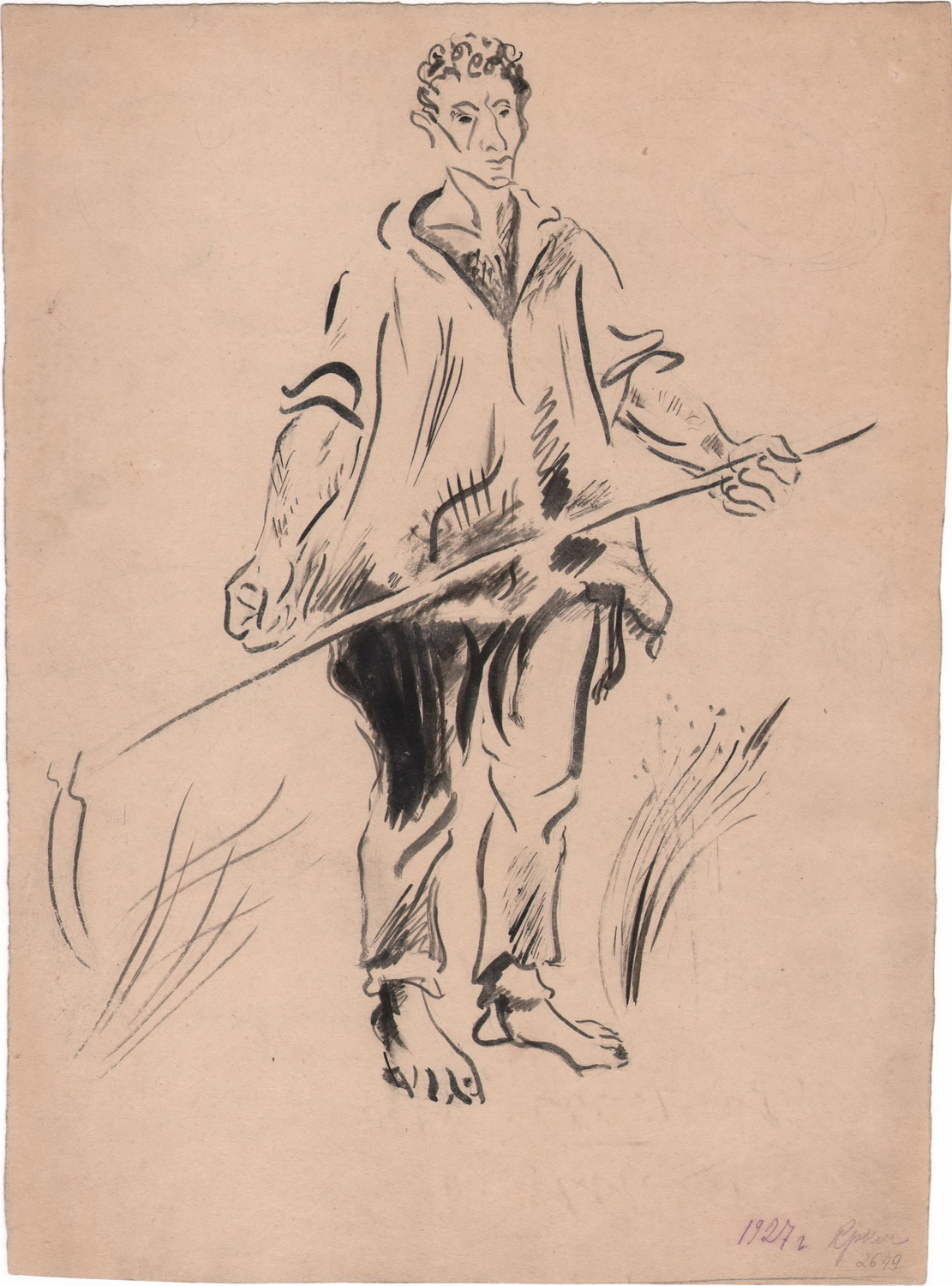

Mark Epstein: “Man with a Scythe”. Ink on paper. 1927. From the series "Jewish collective farms. Crimea"

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian Empire became the epicenter of the movement aimed at the formation of modern Jewish art. For a short, but fruitful period, the young generation of artists, well versed in the achievements of both Western avant-garde art and Jewish traditional culture, managed to synthesize the lessons of cubism, futurism and expressionism with the plastic qualities of folk ornament, which at that time were discovered by ethnographic expeditions. To a large extent, this project became possible thanks to the efforts of the Kultur-Lige – an organization founded in Kiev in 1918 with the goal of developing Jewish secular culture in Yiddish. Its artistic department determined the contours of the new national style through exhibitions, publishing and educational activities. When at the end of 1920 the Communist Party took control over the Kultur-Lige, many of its members left Kiev and settled in other cities. Among those who decided to stay was Mark Epstein – a sculptor and graphic artist, one of the founders and first teachers at the Kultur-Lige art studio.

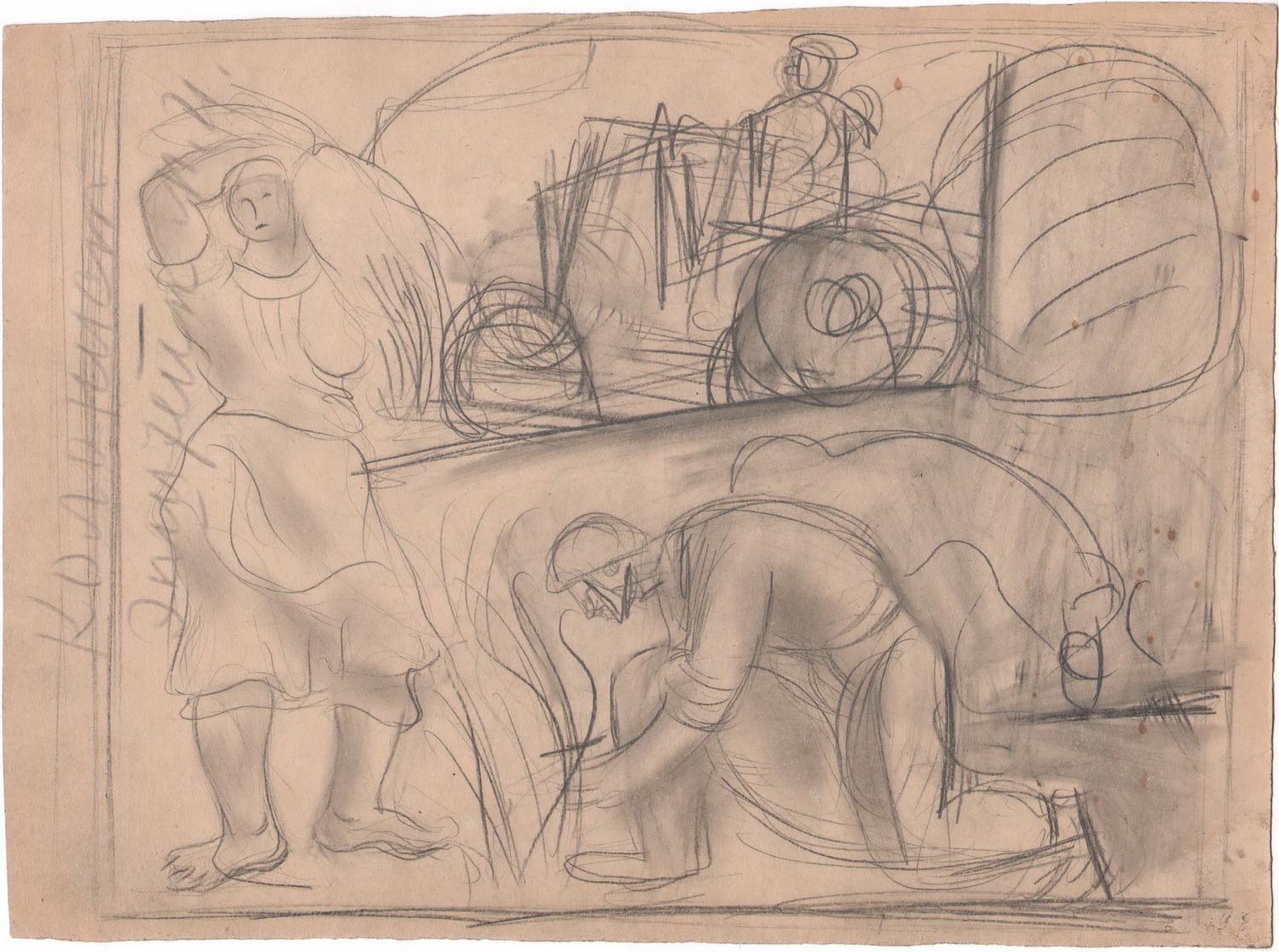

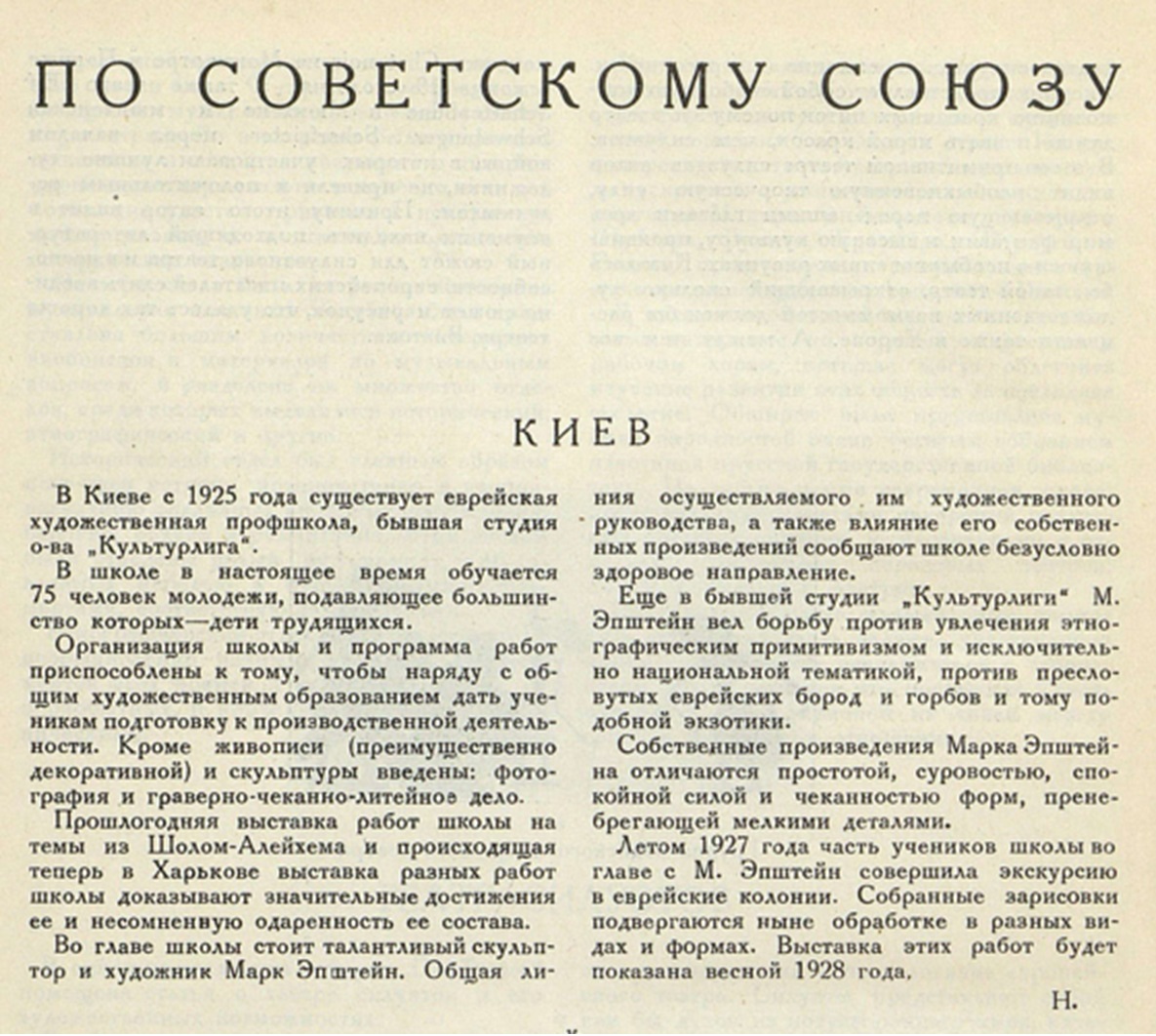

In 1924, the studio came under the control of the Yevsektsiya (the Jewish section of the communist party) and received a new name: the Jewish Art and Industry School. Epstein served as director until the institution’s closure in 1931. Under his leadership, students focused primarily on themes of shtetl life, but not only them. According to a brief report published in the magazine Soviet Art, in the summer of 1927, Epstein and his students traveled to the Jewish colonies of Crimea to make life sketches. As Rybak’s earlier graphic series showed, the theme of the “new Jew” working the land was relevant both for the Soviet authorities, who were promoting the resettlement campaign, and for artists interested in contemporary Jewish life. The decision to undertake this trip may also have been influenced by the fact that the Kiev school was partially financed by the Joint, an American charity that was actively involved in the process of agricultural colonization.

One of the ink drawings made by Epstein during his trip to Crimea now resides in the collection of the Museum of Jewish History in Russia. In the center of the sheet is the figure of a standing colonist holding a scythe. The visual treatment is extremely laconic and cursory, but at the same time a feeling of volume and a monumental sense of form predominates in the sketch. The massive torso, bare feet and powerful arms serve as accent points of the composition, thereby drawing attention to the metamorphosis of Jewish physicality under new circumstances. Despite the obvious physical strength of this mower, the image does not quite fit into the heroic model common in official art and visual culture: the static pose of the hero, devoid of pathos, rather hints at the fatigue of an inexperienced farmer after a hard day's work.